Overview

The TOGAF Architecture Development Method (ADM) is intended to be used as a model to support the definition and

implementation of architecture at multiple levels within an enterprise. As discussed in Part V, Architecture Partitioning , it is not possible to develop a single

architecture that addresses all the needs of all stakeholders. Therefore, the enterprise must be partitioned into

different areas, each of which can be supported by architectures. As discussed in Part V, enterprise architectures are typically

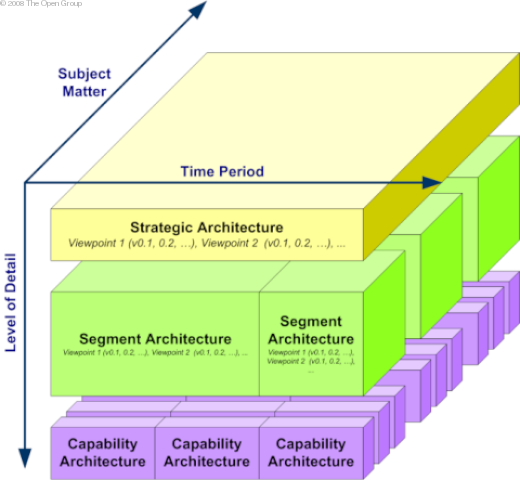

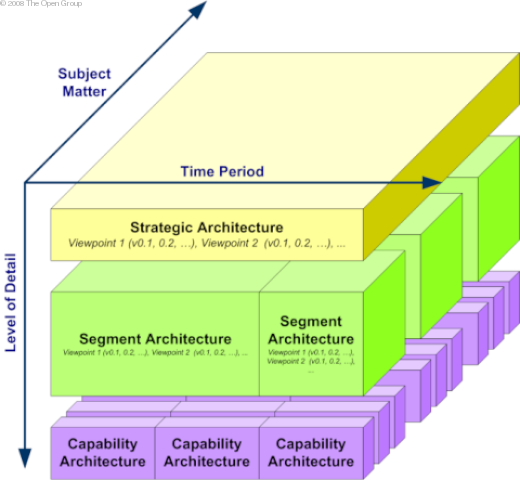

partitioned according to Subject Matter, Time Period, and Level of Detail, as illustrated in Summary Classification Model for Architecture Landscapes .

Figure: Summary Classification Model for Architecture Landscapes

Figure: Summary Classification Model for Architecture Landscapes

This chapter discusses the types of engagement that architects may be required to perform and how the ADM can be used

to co-ordinate the activities of various teams of architects, working at different levels of the enterprise.

Classes of Architecture Engagement

An architecture function or services organization may be called on to assist an enterprise in a number of different

contexts, as architects range from summary to detail, broad to narrow coverage, and current state to future state.

Typically, there are three areas of engagement for architects:

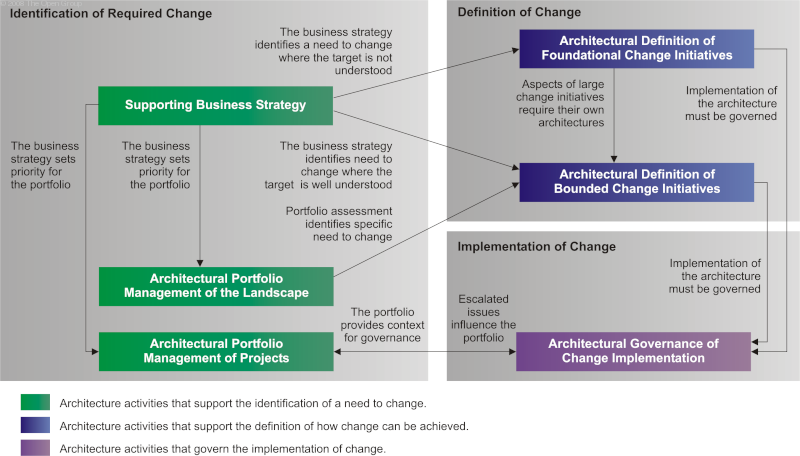

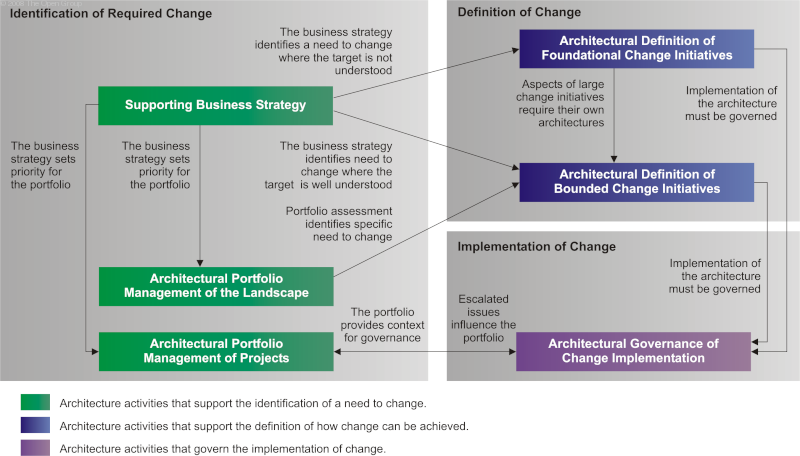

-

Identification of Required Change: Outside the context of any change initiative, architecture can be used as

a technique to provide visibility of the IT capability in order to support strategic decision-making and alignment

of execution.

-

Definition of Change: Where a need to change has been identified, architecture can be used as a technique to

define the nature and extent of change in a structured fashion. Within largescale change initiatives, architectures

can be developed to provide detailed Architecture Definition for change initiatives that are bounded by the scope

of a program or portfolio.

-

Implementation of Change: Architecture at all levels of the enterprise can be used as a technique to provide

design governance to change initiatives by providing big-picture visibility, supplying structural constraints, and

defining criteria on which to evaluate technical decisions.

Classes of Enterprise Architecture Engagement and

the following table show the classes of enterprise architecture engagement.

Figure: Classes of Enterprise Architecture Engagement

Figure: Classes of Enterprise Architecture Engagement

Each of these architecture engagement types is described in the table below.

|

Area of

|

Architecture

|

|

|

Engagement

|

Engagement

|

Description

|

|

Definition of Change

|

Architectural Definition of Foundational Change Initiatives

|

Foundational change initiatives are change efforts that have a known objective, but are not strictly

scoped or bounded by a shared vision or requirements.

In foundational change initiatives, the initial priority is to understand the nature of the problem and

to bring structure to the definition of the problem.

Once the problem is more effectively understood, it is possible to define appropriate solutions and to

align stakeholders around a common vision and purpose.

|

|

Architectural Definition of Bounded Change Initiatives

|

Bounded change initiatives are change efforts that typically arise as the outcome of a prior

architectural strategy, evaluation, or vision.

In bounded change initiatives, the desired outcome is already understood and agreed upon. The focus of

architectural effort in this class of engagement is to effectively elaborate a baseline solution that

addresses the identified requirements, issues, drivers, and constraints.

|

|

Implementation Change

|

Architectural Governance of Change Implementation

|

Once an architectural solution model has been defined, it provides a basis for design and

implementation.

In order to ensure that the objectives and value of the defined architecture are appropriately

realized, it is necessary for continuing architecture governance of the implementation process to

support design review, architecture refinement, and issue escalation.

|

Different classes of architecture engagement at different levels of the enterprise will require focus in specific

areas, as shown below.

|

Engagement Type

|

Focus Iteration Cycles

|

Scope Focus

|

|

Supporting Business Strategy

|

Architecture Context

Architecture Definition

(Baseline First)

|

Broad, shallow consideration given to the Architecture Landscape in order to address a specific

strategic question and define terms for more detailed architecture efforts to address strategy

realization.

|

|

Architectural Portfolio Management of the Landscape

|

Architecture Context

Architecture Definition

(Baseline First)

|

Focus on physical assessment of baseline applications and technology infrastructure to identify

improvement opportunities, typically within the constraints of maintaining business as usual.

|

|

Architectural Portfolio Management of Projects

|

Transition Planning

Architecture Deployment

|

Focus on projects, project dependencies, and landscape impacts to align project sequencing in a way

that is architecturally optimized.

|

|

Architectural Definition of Foundational Change Initiatives

|

Architecture Context

Architecture Definition

(Baseline First)

Transition Planning

|

Focus on elaborating a vision through definition of baseline and identifying what needs to change to

transition the baseline to the target.

|

|

Architectural Definition of Bounded Change Initiatives

|

Architecture Definition

(Target First)

Transition Planning

|

Focus on elaborating the target to meet a previously defined and agreed vision, scope, or set of

constraints. Use the target as a basis for analysis to avoid perpetuation of baseline, sub-optimal

architectures.

|

|

Architectural Governance of Change Implementation

|

Architecture Deployment

|

Use the Architecture Vision, constraints, principles, requirements, Target Architecture definition, and

transition roadmap to ensure that projects realize their intended benefit, are aligned with each other,

and are aligned with wider business need.

|

Developing Architectures at Different Levels

The previous sections have identified that different types of architecture are required to address different

stakeholder needs at different levels of the organization. Each architecture typically does not exist in isolation and

must therefore sit within a governance hierarchy. Broad, summary architectures set the direction for narrow and

detailed architectures.

A number of techniques can be employed to use the ADM as a process that supports such hierarchies of architectures.

Essentially there are two strategies that can be applied:

-

Architectures at different levels can be developed through iterations within a single cycle of the ADM process.

-

Architectures at different levels can be developed through a hierarchy of ADM processes, executed concurrently.

At the extreme ends of the scale, either of these two options can be fully adopted. In practice, an architect is likely

to need to blend elements of each to fit the exact requirements of their Request for Architecture Work.

Each of these approaches is described in the sections below.

ADM Cycle Approaches

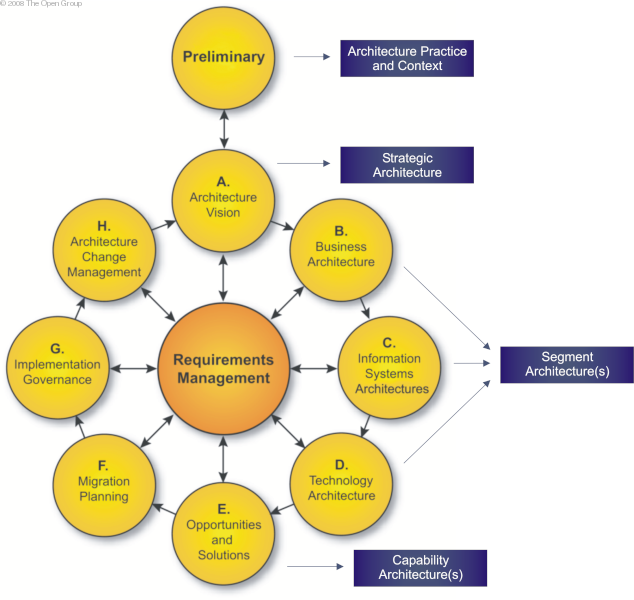

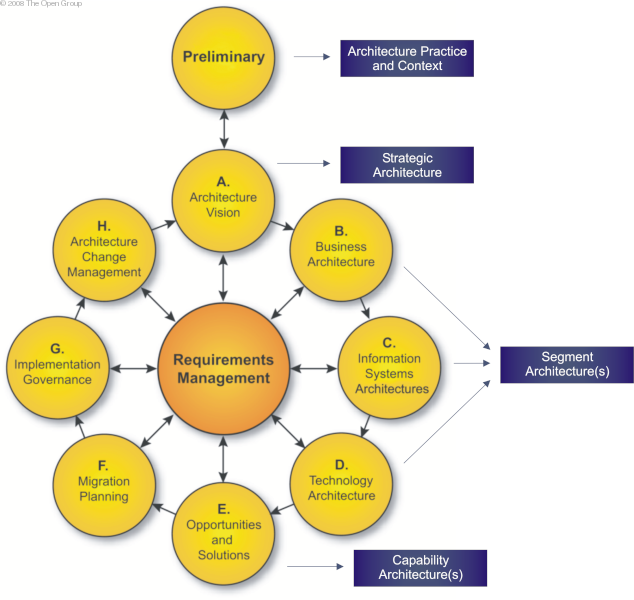

Using Iterations within a Single ADM Cycle

In situations where a single architecture team is tasked with defining architectures at many levels within the

enterprise, it is possible to use iterations within a single ADM cycle to create all required architectures.

Using this approach, the Architecture Vision phase can be used to develop a strategic view of the architecture. Phases

B, C, and D then provide a more detailed and formal architectural view of the landscape for different segments or time

periods. Phases E and F then develop a detailed Migration Plan, which may include even more detailed and specific

Capability Architectures.

A summary of the approach is shown in Iterations within a Single ADM Cycle Example .

Figure: Iterations within a Single ADM Cycle Example

The key benefits of this approach are:

-

It is lightweight, as multiple architectures can be developed against a single Request for Work, project plan, etc.

-

It allows for very close integration of architectures at different levels in the organization.

-

It works well when all architectures are being developed by a single team.

The key limitations of this approach are:

-

It does not explicitly set out governance and change management relationships between the different architectures.

-

It requires all architectures to be completed in sequence and potentially released at the same time. This may delay

the release of strategic architectures or prevent specific Capability Architectures from being developed.

-

Similar architectural activities are repeated within a number of phases within the ADM. It may become difficult to

distinguish the differences between different phases.

Generally speaking, this approach should be used when a number of architectures are being developed within a similar

time period by a single team.

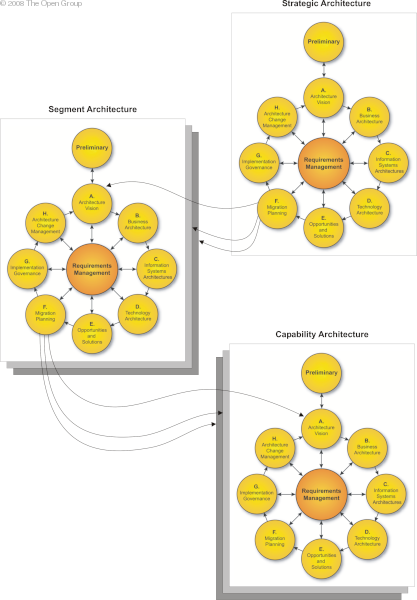

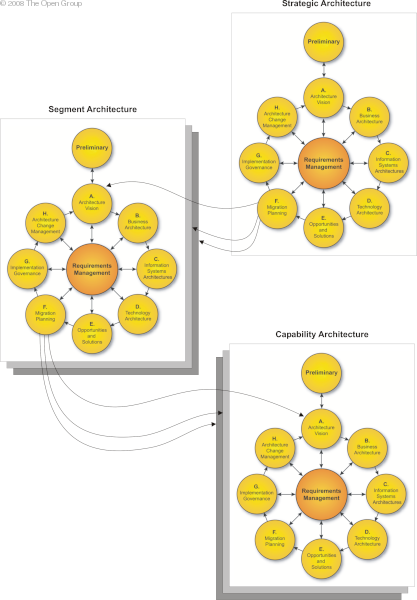

Using a Hierarchy of ADM Processes

In cases where larger-scale architectures need to be developed by a number of different architecture teams, a more

hierarchical application of the ADM may be used. This approach to the ADM uses the Migration Planning phase of one ADM

cycle to initiate new projects, which will also develop architectures. This approach is illustrated in A Hierarchy of ADM Processes Example .

Figure: A Hierarchy of ADM Processes Example

The key benefits of this approach are:

-

It is comprehensive. All ADM activities are carried out at all levels.

-

It establishes explicit governance relationships between architectures.

-

It allows for federated development of architectures at different levels in the organization.

The key limitations of this approach are:

-

It requires the establishment of an enterprise-wide governance hierarchy to be effective.

-

It does not work well when many architectures are being developed by the same team of architects.

Generally speaking, this approach should be used when architectures are being developed over different timelines by

different teams.

|